CHEMICAL HEART

D-Orbitals and Pigments. If a rainbow is light dancing in the air, a pigment is light getting trapped in a stone. When you look at a tube of Ultramarine Blue or Cadmium Red, you aren't looking at an object that creates light. You are looking at a chemical battlefield. The pigment is a substance that has chemically bonded with the light, absorbed most of it, and rejected only a specific sliver. The "reject" is the color you see.

PIGMENTS:The Chemical Heart & D-Orbitals

This is the perfect counterpart to the "Prism" section. While a prism reveals light, a pigment steals it. This is where we move from the physics of waves to the chemistry of the atom. If a rainbow is light dancing in the air, a pigment is light getting trapped in a stone. When you look at a tube of Ultramarine Blue or Cadmium Red, you aren't looking at an object that creates light. You are looking at a chemical battlefield. The pigment is a substance that has chemically bonded with the light, absorbed most of it, and rejected only a specific sliver. The "reject" is the color you see.

THE HEAVY HITTERS: Transition Metals

In the Periodic Table, there is a specific neighborhood responsible for almost all the great historical pigments: The Transition Metals. These are the heavy, complex elements that lie in the center of the table. They are the celebrities of the color world:

Cobalt (Blue/Violet)

Cadmium (Yellows/Reds)

Chromium (Greens)

Copper (Blues/Greens)

Iron (Ochres/Siennas)

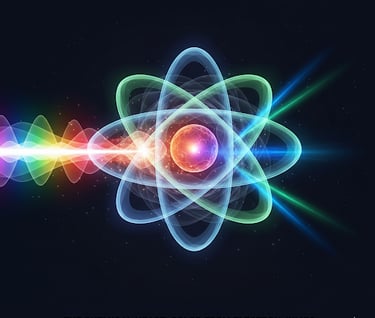

Why these specific metals? Because of the unique shape of their electron "cloud," specifically the d-orbitals.

THE SCIENCE: The Magic of D-Orbitals

This is the "geeky" part where quantum mechanics meets art. Electrons orbit the center of an atom in specific regions called "orbitals." Most atoms have very stable, boring orbitals. But Transition Metals have a special outer shell called the d-orbital. Think of the d-orbital like a shelf that can hold 10 electrons. This section "D-Orbitals," is broken down to be clear, visual, and scientifically accurate. It is designed to visualize the Crystal Field Theory (which is the formal name for the orbital splitting) without using dense formulas.

In isolation: All 5 rooms in this d-orbital shelf are at the same energy height.

In a pigment: When the metal bonds with other atoms (like Oxygen or Sulfur) to make a powder, the electric fields warp the shelf.

The Split: The d-orbital splits into two levels. Some rooms go "upstairs" (higher energy), and some stay "downstairs" (lower energy).

THE ELECTRON JUMP: The Theft of Color

This split creates a gap—a canyon between the lower and upper energy levels. This gap is the secret to color.

White light hits the paint.

An electron sitting in the "downstairs" d-orbital wants to jump to the "upstairs."

To make the jump, it needs energy. It gets this energy by swallowing a photon.

Crucial Detail: It can't just swallow any photon. It has to swallow a photon that matches the exact energy distance of the jump.

THE RESULT

If the gap is small, the electron swallows Red light (low energy). The paint reflects the rest: Blue/Green.

If the gap is large, the electron swallows Blue light (high energy). The paint reflects the rest: Red/Yellow.

The color of your paint is literally the "leftovers." It is the only part of the light spectrum that the d-orbital electrons didn't find tasty enough to eat.

CADMIUM

Why is cadmium toxic but beautiful?

Lianne Wilson

Broker

Jaden Smith

Architect

Jessica Kim

Photographer